Radar | Dec 10,2022

Apr 26 , 2025

By Saliem Fakir , Shuchi Talati

Solar radiation modification, particularly stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), mirrors nature’s volcanic phenomena in hopes of mitigating global warming. However, the potential ripple effects on weather patterns, agriculture, and public health remain largely uncharted waters. In this commentary provided by Project Syndicate (PS), Saliem Fakir, founding Executive director of the African Climate Foundation, and Shuchi Talati, founding executive director of the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering, urge for informed decision-making as African leaders reckon with these low-visibility strategies that could inadvertently widen existing power disparities.

As climate disasters proliferate and intensify, interest has grown in solar radiation modification (SRM), a group of large-scale interventions to lower global temperatures by increasing the amount of sunlight reflected away from Earth. To be clear, the risks and benefits of SRM remain uncertain. But that is all the more reason to design a thoughtful policy approach to these emerging and controversial geoengineering technologies.

This is particularly true in Africa, where SRM efforts could have potentially major economic and social implications, diverting attention or funding from other urgent priorities, such as expanding energy access and supporting a just transition. The continent's policymakers and academics should therefore ensure that discussions about SRM in Africa are guided by a set of principles that emphasise transparency and informed decision-making, and shed light on the biases, power dynamics, and governance gaps surrounding this potential tool.

Research on solar radiation modification is still in its infancy, focused mostly on modelling and small-scale experiments. The most studied option is stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), which involves releasing large amounts of sulfur particles into the upper layer of the atmosphere. The natural analogue of this process – a volcanic eruption – has been shown to decrease temperatures. But the possible environmental and socioeconomic risks associated with SAI, including its effects on everything from precipitation to human health, are not well understood.

Given such uncertainty, African leaders should push for a transparent and equitable approach to researching and governing SRM.

For starters, that means recognising the asymmetrical power dynamic between those funding research in this area and those working to increase oversight of it. This gap will only widen if governments, NGOs, and philanthropic organisations do not start to engage with the fact that private-sector entities are starting to develop SRM. Without a full understanding of the technology's implications, public authorities will not be prepared to establish clear rules for its potential testing and deployment. This could lead to climate-vulnerable countries and communities being sidelined and bearing the brunt of any adverse consequences.

To some extent, this is already happening. Over the past two decades, actors from the Global North – both proponents and opponents of SRM – have dominated the field. Efforts to pursue new research in Global South countries and seek their policy perspectives are encouraging, but remain insufficient. To move beyond colonial forms of engagement, it is essential to facilitate knowledge sharing, rather than pushing for predetermined outcomes. Global South countries can and should forge a responsible path forward for SRM governance, while ensuring that mitigation and adaptation remain top priorities in global climate policy.

African governments are acutely aware of the difficulty of balancing climate-related investment and economic development. Trapped in a cycle of debt distress, many are struggling to restore fiscal stability, finance counter-cyclical measures to put their economies on a more sustainable trajectory, and adapt to the growing climate threat. A key concern for African stakeholders is that there are still more questions than answers about the consequences of SRM, raising questions about whether its effects will ultimately be more helpful or harmful. At the same time, it may well divert resources from other investments that are more likely to drive long-term economic growth and development.

A series of dialogues organised by the African Climate Foundation and the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering came to many of the same conclusions, including that SRM must not exacerbate inequalities and undermine climate action, and should be governed accordingly. The meetings also highlighted the need for better information sharing and capacity building in African governments, civil society, and academia concerning SRM, as many of the continent's leaders lack knowledge about these technologies.

Developing an effective climate strategy – from accelerating the uptake of renewables to decarbonising industry and responsibly exploring controversial technologies like SRM – requires in-depth knowledge of the topic at hand. Multistakeholder dialogue and grassroots engagement – essential components of any geoengineering strategy – require it. Rather than simply arguing for or against SRM, these efforts should focus on collecting diverse perspectives and obtaining local input by increasing transparency, debating potential risks, and emphasising that no single technology is a panacea.

While African countries undoubtedly have more immediate concerns than SRM, policymakers and stakeholders on the continent should become better prepared to engage with this rapidly evolving field. The design and governance of SRM will play a crucial part in determining its impact, and developing a nuanced understanding of these early-stage technologies across Africa can help inform long-term decision-making.

As global warming accelerates, engaging with SRM at the regional, national, and local levels will be crucial to creating an inclusive, transparent, and accountable solar-geoengineering ecosystem on the continent.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 26,2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1304]

Radar | Dec 10,2022

Radar | Jan 21,2023

Radar | Sep 14,2024

My Opinion | Dec 02,2023

Radar | Jul 31,2021

Radar | Mar 18,2023

Viewpoints | Jan 22,2022

Radar | Sep 19,2020

Radar | Sep 22,2024

Radar | May 27,2023

My Opinion | 128051 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 124267 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 122381 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 120234 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

Apr 26 , 2025

Benjamin Franklin famously quipped that “nothing is certain but death and taxes.�...

Apr 20 , 2025

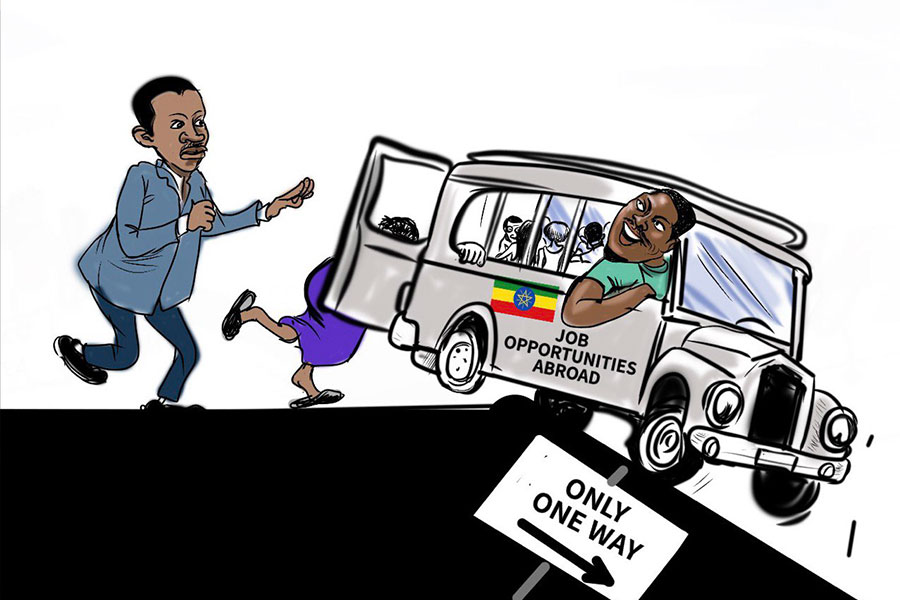

Mufariat Kamil, the minister of Labour & Skills, recently told Parliament that he...

Apr 13 , 2025

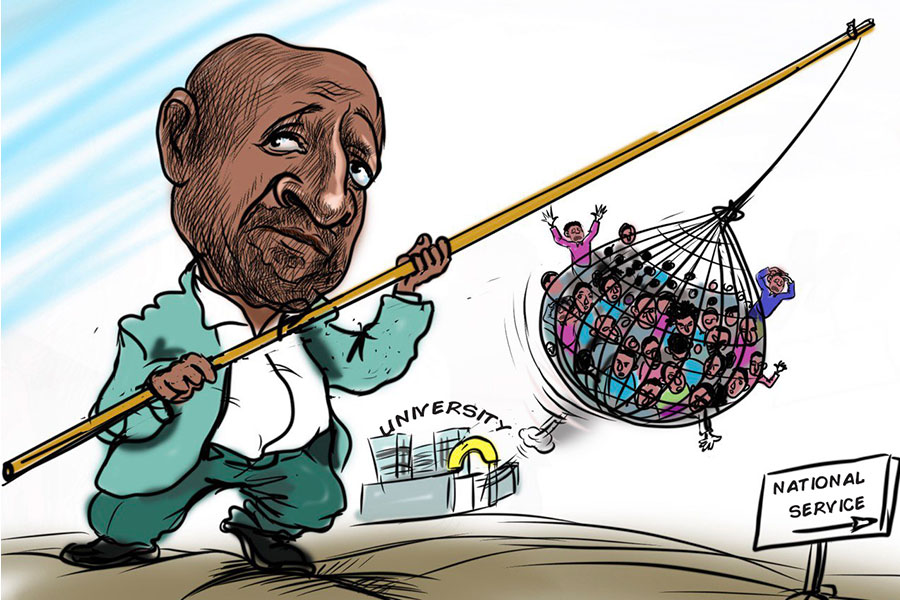

The federal government will soon require one year of national service from university...

Apr 6 , 2025

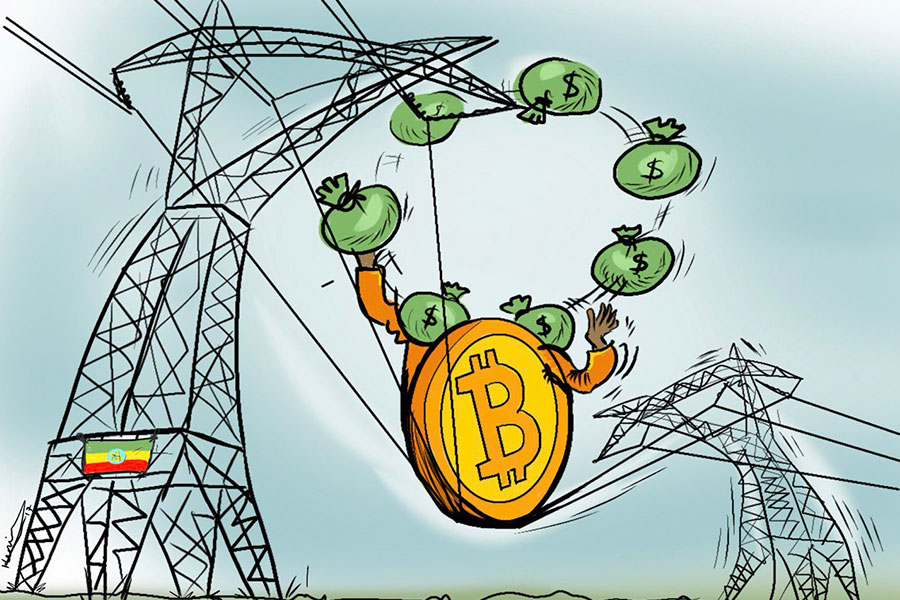

Last week, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group...

Apr 26 , 2025

Neway Magersa (Left), president of Sinqee Bank, shared a lighter moment at the Skylight Hotel on Africa Avenue and chuckled with Oromia Regi...

Apr 27 , 2025 . By BEZAWIT HULUAGER

A controversial decision to clear a large tract of land in Addis Abeba's Wereda 1, around Flamingo and th...

Apr 27 , 2025 . By AKSAH ITALO

Key Takeaways A federal court dismissed Zewdinesh Getahun's ownership claim as time-barred, requir...

Apr 27 , 2025 . By AKSAH ITALO

Key Takeaways: Ethiopian drug makers are seeking unconditional guarantees from the state-owned Eth...